## Importing libraries

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Python intensive, day 5

Pandas

Motivating Example

Today we are going to continue learning to apply python to data science by introducing another python library that is similar to numpy called pandas.

Consider: based on what we've learned the past several days, what are some limitations of

numpy? Can you think of any tasks you might want to do or analysis you might like to perform that would be difficult withnumpy? Does this give you a guess as to whatpandasspecializes in?

Answer: numpy is specialized primarily for numerical operations, e.g. matrix multiplication, vector math, etc., but is more limited when dealing with other data types such as string, python objects, etc. In contrast, pandas objects are able to handle mixed data easily! As you will often run into this type of data when doing bioinformatics, pandas can be very useful.

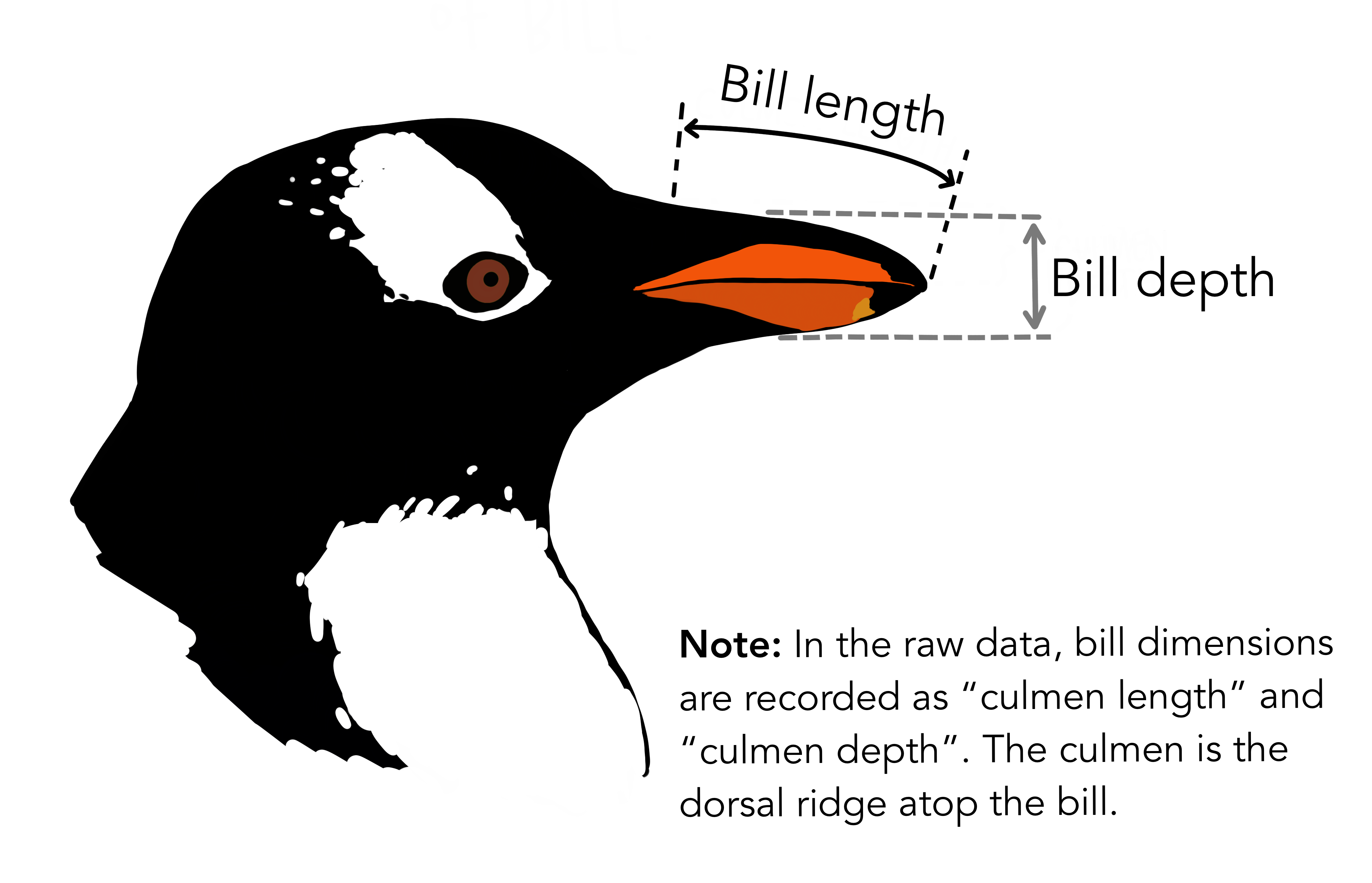

Before we dive into the syntax, let's take a look at an example real-world application of pandas for a task that you might commonly face in biology. We are going to use the "Palmer penguins" dataset, which is a collection of various biometric data for several different penguin species and is a commonly used example dataset. Let's take a quick look at what the data looks like.

In the Palmer penguins dataset, each row represents an individual penguin, and each column represent a different measurement or characteristic of the penguin, such as its body mass or island of origin. The data are organized in this way so that variables (things we may want to compare against each other) are the columns while observations (the individual penguins) are the rows. This is a common way to organize data in data science and is called tidy data. Tidy data formatting also makes it easy to use code to manipulate and analyze, which we will see in this lesson.

penguins = pd.read_csv('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/rfordatascience/tidytuesday/main/data/2020/2020-07-28/penguins.csv')

penguins.head()

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2007 |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | female | 2007 |

| 2 | Adelie | Torgersen | 40.3 | 18.0 | 195.0 | 3250.0 | female | 2007 |

| 3 | Adelie | Torgersen | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2007 |

| 4 | Adelie | Torgersen | 36.7 | 19.3 | 193.0 | 3450.0 | female | 2007 |

Here is an example of a transformation that we will be able to do with pandas that would be difficult to do manually or with numpy. We can summarize the data by calculating the average body mass (in kg) of each penguin species, broken up by sex. Using a few lines of code we can go from our raw data to a table that looks like this:

| species | sex | body_mass_kg |

|---|---|---|

| Adelie | female | 3.368836 |

| Adelie | male | 4.043493 |

| Chinstrap | female | 3.527206 |

| Chinstrap | male | 3.938971 |

| Gentoo | female | 4.679741 |

| Gentoo | male | 5.484836 |

Now, let's get started learning how this is done!

Pandas Series

A Series is the simplest data structure in Pandas. They are one dimensional (1D) objects composed of a single data type of any variety (string, integers); you can basically think of them as a single column in a spreadsheet. They are similar to arrays in numpy, however unlike those other 1D structures Series also have label-based indexing, meaning each element in the object can be accessed by specifying its specific label. In that way, they are similar to dictionaries in python.

We can manually create a Series in several ways:

Using the pd.Series() function, we provide it the data we want to store as a list, and optionally we can give each row of the data a label using the index argument. If we don't give it the index argument, it will automatically assign a numerical index to each row starting from 0.

When we print the Series, it will display as a column with the index on the left and the data on the right. The type of data being held in the series will be displayed at the bottom of the output.

0 10 1 20 2 30 3 40 dtype: int64

a 10 b 20 c 30 d 40 dtype: int64

Another way to create a Series is to convert a (non-nested) dictionary into a Series. The keys of the dictionary will become the index labels while the values will become the data.

# Converting from dictionary to series

my_dictionary = {'first': 10, 'second': 20, 'third': 30}

s2 = pd.Series(my_dictionary)

print(s2)

first 10 second 20 third 30 dtype: int64

We can then access specific elements in the Series by referring to its index label enclosed in quotes and brackets. This is very similar to how a dictionary works!

10 10 20

Multi-indexed Series

Series objects may have multiple levels of indices. We call this multi-indexed. Using layers of indexing is a way of representing two-dimensional data within a one-dimensional Series object. Some people really like using multi-indexed Series. You can create a multi-indexed series by passing a list of lists to the index argument of the pd.Series() function. The first list will be the outermost level of the index, the second list will be the next level, and so on.

my_index = [["California", "California", "New York", "New York", "Texas", "Texas"],

[2001, 2002, 2001, 2002, 2001, 2002]]

my_values = [1.5, 1.7, 3.6, 4.2, 3.2, 4.5]

s3 = pd.Series(my_values, index=my_index)

print(s3)

California 2001 1.5

2002 1.7

New York 2001 3.6

2002 4.2

Texas 2001 3.2

2002 4.5

dtype: float64

Retrieving an item from this data structure is similar to a nested dictionary, using successive [] notation. Or, you can passs it a tuple. You must pass the index labels in the order they were created (left to right)

print(s3["California"])

print("---")

print(s3["California"][2001])

print("---")

print(s3[("California", 2001)])

print("---")

# you can also use slicing to select multiple elements

print(s3["California":"New York"])

2001 1.5

2002 1.7

dtype: float64

---

1.5

---

1.5

---

California 2001 1.5

2002 1.7

New York 2001 3.6

2002 4.2

dtype: float64

In our work, we typically don't use multi-indexed Series. However, they are often the output of pandas functions, so it's good to know how to work with them. If you don't like the idea of multi-indexed Series, you can always convert them to a DataFrame using the reset_index() method.

| level_0 | level_1 | 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | California | 2001 | 1.5 |

| 1 | California | 2002 | 1.7 |

| 2 | New York | 2001 | 3.6 |

| 3 | New York | 2002 | 4.2 |

| 4 | Texas | 2001 | 3.2 |

| 5 | Texas | 2002 | 4.5 |

Pandas DataFrame

While Series is a "one-dimensional" data structure, DataFrames are two-dimensional. Where Series can only contain one type of data, the pandas DataFrame can have a combination of numerical and categorical data. Additionally, DataFrames allow you do have labels for your rows and columns.

DataFrames are essentially a collection of Series objects. You can also think of python DataFrames as spreadsheets from Excel or dataframes from R.

Let's manually create a simple dataframe in pandas to showcase their behavior. In the below code, we create a dictionary where the keys are the column names and the values are lists of data. We then pass this dictionary to the pd.DataFrame() function to create a DataFrame.

When we print the DataFrame, it will display as a table with the column names at the top and the data below. The index (in this case, automatically generated numerical index starting at 0) will be displayed on the left side of the table.

tournamentStats = {

"wrestler": ["Terunofuji", "Ura", "Shodai", "Takanosho"],

"wins": [13, 6, 10, 12],

"rank": ["yokozuna", "maegashira2", "komusubi", "maegashira6"]

}

#Converting to a pandas DataFrame

sumo = pd.DataFrame(tournamentStats)

print(sumo)

wrestler wins rank

0 Terunofuji 13 yokozuna

1 Ura 6 maegashira2

2 Shodai 10 komusubi

3 Takanosho 12 maegashira6

Pandas dataframes have many attributes, including shape, columns, index, dtypes. These are useful for understanding the structure of the dataframe.

print(sumo.shape)

print("---")

print(sumo.columns)

print("---")

print(sumo.index)

print("---")

print(sumo.dtypes)

(4, 3) --- Index(['wrestler', 'wins', 'rank'], dtype='object') --- RangeIndex(start=0, stop=4, step=1) --- wrestler object wins int64 rank object dtype: object

Pandas DataFrames also have the handy info() function that summarizes the contents of the dataframe, including counts of the non-null values of each column and the data type of each column.

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'> RangeIndex: 4 entries, 0 to 3 Data columns (total 3 columns): # Column Non-Null Count Dtype --- ------ -------------- ----- 0 wrestler 4 non-null object 1 wins 4 non-null int64 2 rank 4 non-null object dtypes: int64(1), object(2) memory usage: 228.0+ bytes

Selecting data in a Pandas dataframe

As with series objects, pandas dataframes rows and columns are explicitly indexed, which means that every row and column has a label associated with it. You can think of the explicit indices as the being the names of the rows and the names of the columns.

Unfortunately, in pandas the syntax for subsetting rows v.s. columns is different and can get a little confusing, so let's go through several different use cases.

Selecting columns

We can always check the names of the columns in a Pandas dataframe byt using the built-in .columns method, which simply lists the column index:

Index(['wrestler', 'wins'], dtype='object')

If we want to refer to a specific column, we can specify its index (enclosed in double quotes) inside of square brackets [] like so:

0 Terunofuji 1 Ura 2 Shodai 3 Takanosho Name: wrestler, dtype: object

If we want to refer to multiple columns, we need to pass the columns as a list by enclosing the column indices in square brackets, so you will end up with double brackets:

| wrestler | rank | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Terunofuji | yokozuna |

| 1 | Ura | maegashira2 |

| 2 | Shodai | komusubi |

| 3 | Takanosho | maegashira6 |

Selecting rows:

The syntax for selecting specific rows is slightly different. Let's first check the labels of the row index; to do this we use the .index method:

RangeIndex(start=0, stop=4, step=1)

Here we can see that while the column index labels were strings, the row index labels are numerical values, in this case 0 thru 3. If we wanted to pull out the first row, we need to specify its index label (0) in combination with the .loc method (which is required for rows):

If we want to select multiple rows, like with columns we need to pass it as a list using the double brackets. If we want to specify a range of rows (i.e. from this row to that row), we don't use double brackets and instead use ::

Note that in this case the row index labels are numbers, but do not have to be numerical, and can have string labels similar to columns. Let's show how we could change the row index labels by taking the column with the wrestler's rank and setting it as the index label (note that the labels should be unique!):

wrestler wins

rank

yokozuna Terunofuji 13

maegashira2 Ura 6

komusubi Shodai 10

maegashira6 Takanosho 12

wrestler Terunofuji wins 13 Name: yokozuna, dtype: object

We also need to use .loc if we are referring to a specific row AND column, e.g.:

Shodai

If we want to purely use numerical indexing, we can use the .iloc() method. If you use .iloc(), you can index a DataFrame just as you would a numpy array.

| wrestler | wins | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Terunofuji | 13 |

| 1 | Ura | 6 |

There are many ways to select subsets of a dataframe. The rows and columns of a dataframe can be referred to either by their integer position or by their indexed name. Typically, for columns, you'll use the indexed name and can just do [] with the name of the column. For rows, if you want to use the integer position, you will use .iloc[]. If you want to use the index name, you will use .loc[].

For reference, here's a handy table on the best ways to index into a dataframe:

| Action | Named index | Integer Position |

|---|---|---|

| Select single column | df['column_name'] |

df.iloc[:, column_position] |

| Select multiple columns | df[['column_name1', 'column_name2']] |

df.iloc[:, [column_position1, column_position2]] |

| Select single row | df.loc['row_name'] |

df.iloc[row_position] |

| Select multiple rows | df.loc[['row_name1', 'row_name2']] |

df.iloc[[row_position1, row_position2]] |

Exercise: we'll use the penguins dataset from our initial example. 1) Print the 'species' column 2) Print the first five columns and first five rows 3) Print the columns "species", "island", and "sex" and the first ten rows of the dataframe

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'> RangeIndex: 344 entries, 0 to 343 Data columns (total 8 columns): # Column Non-Null Count Dtype --- ------ -------------- ----- 0 species 344 non-null object 1 island 344 non-null object 2 bill_length_mm 342 non-null float64 3 bill_depth_mm 342 non-null float64 4 flipper_length_mm 342 non-null float64 5 body_mass_g 342 non-null float64 6 sex 333 non-null object 7 year 344 non-null int64 dtypes: float64(4), int64(1), object(3) memory usage: 21.6+ KB

# Your code here

print(penguins['species'])

print("---")

print(penguins.iloc[0:5,0:5])

print("---")

print(penguins.loc[0:10, ['species', 'island', 'sex']])

0 Adelie

1 Adelie

2 Adelie

3 Adelie

4 Adelie

...

339 Chinstrap

340 Chinstrap

341 Chinstrap

342 Chinstrap

343 Chinstrap

Name: species, Length: 344, dtype: object

---

species island bill_length_mm bill_depth_mm flipper_length_mm

0 Adelie Torgersen 39.1 18.7 181.0

1 Adelie Torgersen 39.5 17.4 186.0

2 Adelie Torgersen 40.3 18.0 195.0

3 Adelie Torgersen NaN NaN NaN

4 Adelie Torgersen 36.7 19.3 193.0

---

species island sex

0 Adelie Torgersen male

1 Adelie Torgersen female

2 Adelie Torgersen female

3 Adelie Torgersen NaN

4 Adelie Torgersen female

5 Adelie Torgersen male

6 Adelie Torgersen female

7 Adelie Torgersen male

8 Adelie Torgersen NaN

9 Adelie Torgersen NaN

10 Adelie Torgersen NaN

Importing data to pandas

One of the most useful features of pandas DataFrames is its ability to easily perform complex data transformations. This makes it a powerful tool for cleaning, filtering, and summarizing tabular data. As shown above, we can manually create a DataFrame from scratch, but more commonly you will want to read in data from an external source, such as the output of a bioinformatic program, and do some manipulation of it. Let's read some data into a DataFrame to demonstrate.

Below you can see an example of how to read files into pandas using the pd.read_csv() function. The csv stands for 'comma-separated values', which means by defaults it will assume that our columns are separated by commas; if we wanted to change the delimiter (e.g. in the case of a tab-separated file), we can set the delimiter explicitly using the sep= argument.

penguins = pd.read_csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/rfordatascience/tidytuesday/main/data/2020/2020-07-28/penguins.csv", sep=',')

# The head() function from pandas prints only the first N lines of a dataframe (default: 10)

penguins.head()

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2007 |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | female | 2007 |

| 2 | Adelie | Torgersen | 40.3 | 18.0 | 195.0 | 3250.0 | female | 2007 |

| 3 | Adelie | Torgersen | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2007 |

| 4 | Adelie | Torgersen | 36.7 | 19.3 | 193.0 | 3450.0 | female | 2007 |

When importing data into a DataFrame, pandas automatically detects what data type each column should be. For example, if the column contains only numbers, it will be imported as an floating point or integer data type. If the column contains strings or a mixture of strings and numbers, it will be imported as an "object" data type. Below are the different data types for the penguins column.

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'> RangeIndex: 344 entries, 0 to 343 Data columns (total 8 columns): # Column Non-Null Count Dtype --- ------ -------------- ----- 0 species 344 non-null object 1 island 344 non-null object 2 bill_length_mm 342 non-null float64 3 bill_depth_mm 342 non-null float64 4 flipper_length_mm 342 non-null float64 5 body_mass_g 342 non-null float64 6 sex 333 non-null object 7 year 344 non-null int64 dtypes: float64(4), int64(1), object(3) memory usage: 21.6+ KB

Looping through a dataframe

As a note, if we want to go through a dataframe line-by-line (i.e. row by row), because both the rows and columns are indexed it requires slightly more syntax than looping through other data structures (e.g. a dictionary or list). Specifically we need to use the .iterrows() method to make the data frame iterable. The .iterrows() method outputs each row as a Series object with a row index and the column:

for index, row in penguins.iterrows():

print(f"Row index: {index}, {row['species']}, {row['island']}")

This can be slow for very large dataframes, but is useful if you need to perform actions on individual rows.

Modifying a dataframe

Now that we have our external data read into a DataFrame, we can begin to work our magic. If you have ever worked with tidyverse in the R language some of this might look familiar to you, as pandas serves a similar role and can do many of the same functions. Let's look at several useful common examples.

Filtering

When we discussed indexing, we looked at how we can select specific rows and columns in a dataframe, but often we will want to select rows based on a certain condition, e.g. in the dataframe that we just imported, only take the rows where the 'body_mass_g' column has a value greater than a given number. We can do this easily by specifying which column to filter on and a boolean statement, like so:

print(penguins[penguins['flipper_length_mm'] == 181.0])

#Saving as new data frame:

penguins_filtered = penguins[penguins['body_mass_g'] > 3300]

penguins_filtered.head()

species island bill_length_mm bill_depth_mm flipper_length_mm \

0 Adelie Torgersen 39.1 18.7 181.0

6 Adelie Torgersen 38.9 17.8 181.0

38 Adelie Dream 37.6 19.3 181.0

58 Adelie Biscoe 36.5 16.6 181.0

108 Adelie Biscoe 38.1 17.0 181.0

293 Chinstrap Dream 58.0 17.8 181.0

296 Chinstrap Dream 42.4 17.3 181.0

body_mass_g sex year

0 3750.0 male 2007

6 3625.0 female 2007

38 3300.0 female 2007

58 2850.0 female 2008

108 3175.0 female 2009

293 3700.0 female 2007

296 3600.0 female 2007

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2007 |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | female | 2007 |

| 4 | Adelie | Torgersen | 36.7 | 19.3 | 193.0 | 3450.0 | female | 2007 |

| 5 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.3 | 20.6 | 190.0 | 3650.0 | male | 2007 |

| 6 | Adelie | Torgersen | 38.9 | 17.8 | 181.0 | 3625.0 | female | 2007 |

We can get more advanced with our filtering logic by adding multiple conditions and the following logical operators:

&: "and"|: "or"~: "not"

Note that these are different logical operators than we have previously learned in base python!

If using multiple conditions, be sure to enclose each of them in parentheses!

penguins_filtered = penguins[(penguins['body_mass_g'] > 3300) & (penguins['bill_length_mm'] > 38)]

penguins_filtered.head()

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2007 |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | female | 2007 |

| 5 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.3 | 20.6 | 190.0 | 3650.0 | male | 2007 |

| 6 | Adelie | Torgersen | 38.9 | 17.8 | 181.0 | 3625.0 | female | 2007 |

| 7 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.2 | 19.6 | 195.0 | 4675.0 | male | 2007 |

Pandas also has a helper function called .isin() that is similar to the in operator in base python. It allows you to filter a dataframe based on whether a column value is in a list of values.

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2007 |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | female | 2007 |

| 2 | Adelie | Torgersen | 40.3 | 18.0 | 195.0 | 3250.0 | female | 2007 |

| 3 | Adelie | Torgersen | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2007 |

| 4 | Adelie | Torgersen | 36.7 | 19.3 | 193.0 | 3450.0 | female | 2007 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 271 | Gentoo | Biscoe | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2009 |

| 272 | Gentoo | Biscoe | 46.8 | 14.3 | 215.0 | 4850.0 | female | 2009 |

| 273 | Gentoo | Biscoe | 50.4 | 15.7 | 222.0 | 5750.0 | male | 2009 |

| 274 | Gentoo | Biscoe | 45.2 | 14.8 | 212.0 | 5200.0 | female | 2009 |

| 275 | Gentoo | Biscoe | 49.9 | 16.1 | 213.0 | 5400.0 | male | 2009 |

276 rows × 8 columns

Exercise: filter the dataframe to only keep the birds observed in the

year2007 and with abill_length_mmgreater than 38mm

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2007 |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | female | 2007 |

| 2 | Adelie | Torgersen | 40.3 | 18.0 | 195.0 | 3250.0 | female | 2007 |

| 5 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.3 | 20.6 | 190.0 | 3650.0 | male | 2007 |

| 6 | Adelie | Torgersen | 38.9 | 17.8 | 181.0 | 3625.0 | female | 2007 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 297 | Chinstrap | Dream | 48.5 | 17.5 | 191.0 | 3400.0 | male | 2007 |

| 298 | Chinstrap | Dream | 43.2 | 16.6 | 187.0 | 2900.0 | female | 2007 |

| 299 | Chinstrap | Dream | 50.6 | 19.4 | 193.0 | 3800.0 | male | 2007 |

| 300 | Chinstrap | Dream | 46.7 | 17.9 | 195.0 | 3300.0 | female | 2007 |

| 301 | Chinstrap | Dream | 52.0 | 19.0 | 197.0 | 4150.0 | male | 2007 |

89 rows × 8 columns

We can also filter based on strings, not just numbers! For this, you will want to use a string matching function from python, such as .str.contains() (which also a partial match), .str.startswith() (checks to see if a value starts with a given string), or others.

penguins_filtered = penguins[penguins['species'].str.contains('Adel', case=False)]

penguins_filtered

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2007 |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | female | 2007 |

| 2 | Adelie | Torgersen | 40.3 | 18.0 | 195.0 | 3250.0 | female | 2007 |

| 3 | Adelie | Torgersen | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2007 |

| 4 | Adelie | Torgersen | 36.7 | 19.3 | 193.0 | 3450.0 | female | 2007 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 147 | Adelie | Dream | 36.6 | 18.4 | 184.0 | 3475.0 | female | 2009 |

| 148 | Adelie | Dream | 36.0 | 17.8 | 195.0 | 3450.0 | female | 2009 |

| 149 | Adelie | Dream | 37.8 | 18.1 | 193.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2009 |

| 150 | Adelie | Dream | 36.0 | 17.1 | 187.0 | 3700.0 | female | 2009 |

| 151 | Adelie | Dream | 41.5 | 18.5 | 201.0 | 4000.0 | male | 2009 |

152 rows × 8 columns

In the above example, this code looks for the string 'Adel' (case-insensitive, as we specify case=False) and only takes rows that contain the string somewhere in the species column.

Missing data in DataFrames

Missing data in a DataFrame is represeted by NaN (Not a Number). Pandas handles missing data in some specific ways, which we will discuss in this section.

Missing numbers are propagated through the DataFrame when doing arithmetic operations. In the example below, when we try to sum the two columns together element-wise, any row where one of the columns has a missing value will result in the sum being NaN.

0 NaN 1 NaN 2 NaN 3 7.0 dtype: float64

When using descriptive statistics and computational methods like .sum(), .mean(), pandas will ignore missing values and treat them like zero.

5.0 2.5

This behavior can be changed by using the skipna argument, which is True by default. If you set skipna=False, pandas will treat missing values as NaN and will not ignore them, resulting in the whole operation returning NaN.

nan

One very useful function to know is how to get rid of rows with missing data in them, as including them can often cause errors in downstream analysis or skew your results. There is a convenient function built in to pandas that does this called .dropna(). By default, it will drop any row that has a missing value in any column. This may not always be what you want. You can specify which columns to look at using the subset arugment.

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'> Index: 333 entries, 0 to 343 Data columns (total 8 columns): # Column Non-Null Count Dtype --- ------ -------------- ----- 0 species 333 non-null object 1 island 333 non-null object 2 bill_length_mm 333 non-null float64 3 bill_depth_mm 333 non-null float64 4 flipper_length_mm 333 non-null float64 5 body_mass_g 333 non-null float64 6 sex 333 non-null object 7 year 333 non-null int64 dtypes: float64(4), int64(1), object(3) memory usage: 23.4+ KB

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'> Index: 342 entries, 0 to 343 Data columns (total 8 columns): # Column Non-Null Count Dtype --- ------ -------------- ----- 0 species 342 non-null object 1 island 342 non-null object 2 bill_length_mm 342 non-null float64 3 bill_depth_mm 342 non-null float64 4 flipper_length_mm 342 non-null float64 5 body_mass_g 342 non-null float64 6 sex 333 non-null object 7 year 342 non-null int64 dtypes: float64(4), int64(1), object(3) memory usage: 24.0+ KB

Alternatively, you may want to fill in missing values with a specific value. You can do this using the .fillna() method.

Calculating new columns

Let's say we will want to create a new column in our dataframe by applying some function to existing columns. For instance, in the dataframe of penguins data that we have been using, we want a column that normalizes body_mass_g column by performing a z-transform. A z-transform is the value minus the mean of the column divided by the standard deviation of the column.

First, we put the name of the new column, body_mass_z in square brackets after our penguin DataFrame variable. Then we pull out the body_mass_g column and perform the calculation, using helper methods like .mean() and .std(), on the right side of the assignment operator. This syntax is similar to creating a new key in a dictionary.

# Z-transform the body mass column

penguins["body_mass_z"] = (penguins["body_mass_g"] - penguins["body_mass_g"].mean()) / penguins["body_mass_g"].std()

penguins.head(10)

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | body_mass_z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2007 | -0.563317 |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | female | 2007 | -0.500969 |

| 2 | Adelie | Torgersen | 40.3 | 18.0 | 195.0 | 3250.0 | female | 2007 | -1.186793 |

| 3 | Adelie | Torgersen | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2007 | NaN |

| 4 | Adelie | Torgersen | 36.7 | 19.3 | 193.0 | 3450.0 | female | 2007 | -0.937403 |

| 5 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.3 | 20.6 | 190.0 | 3650.0 | male | 2007 | -0.688012 |

| 6 | Adelie | Torgersen | 38.9 | 17.8 | 181.0 | 3625.0 | female | 2007 | -0.719186 |

| 7 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.2 | 19.6 | 195.0 | 4675.0 | male | 2007 | 0.590115 |

| 8 | Adelie | Torgersen | 34.1 | 18.1 | 193.0 | 3475.0 | NaN | 2007 | -0.906229 |

| 9 | Adelie | Torgersen | 42.0 | 20.2 | 190.0 | 4250.0 | NaN | 2007 | 0.060160 |

Exercise: We can use multiple columns in the calculation of the new column. Create a column that contains the volume of the penguin's beak by assuming it is a cylinder, with

bill_length_mmas the height andbill_depth_mmas the diameter.Hint: The volume of a cylinder is given by the formula $V = \pi r^2 h$, where $r$ is the radius (half the diameter) and $h$ is the height.

# Your code here

penguins["bill_volume"] = (penguins["bill_depth_mm"]/2)**2 * np.pi * penguins["bill_length_mm"]

penguins.head()

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | bill_volume | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2007 | 10738.654055 |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | female | 2007 | 9392.592344 |

| 2 | Adelie | Torgersen | 40.3 | 18.0 | 195.0 | 3250.0 | female | 2007 | 10255.100899 |

| 3 | Adelie | Torgersen | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2007 | NaN |

| 4 | Adelie | Torgersen | 36.7 | 19.3 | 193.0 | 3450.0 | female | 2007 | 10736.693701 |

Summarizing your data

Another common task in data analysis is to calculate summary statistics of your data. Pandas as a number of helper methods like .mean(), .median(), .count(), unique(), etc. that can be used to describe your data. Pandas DataFrames has a handy .describe() method that will give you a summary of the data in each column. By default, it will calculate the count, mean, standard deviation, minimum, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile, and maximum of each numerical column. However, if you give it the include='all' or include='object' argument, it will also include the count, unique, top, and freq (of top) of each categorical column.

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | bill_volume | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 344 | 344 | 342.000000 | 342.000000 | 342.000000 | 342.000000 | 333 | 344.000000 | 342.000000 |

| unique | 3 | 3 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2 | NaN | NaN |

| top | Adelie | Biscoe | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | male | NaN | NaN |

| freq | 152 | 168 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 168 | NaN | NaN |

| mean | NaN | NaN | 43.921930 | 17.151170 | 200.915205 | 4201.754386 | NaN | 2008.029070 | 10216.041172 |

| std | NaN | NaN | 5.459584 | 1.974793 | 14.061714 | 801.954536 | NaN | 0.818356 | 2468.270185 |

| min | NaN | NaN | 32.100000 | 13.100000 | 172.000000 | 2700.000000 | NaN | 2007.000000 | 5782.155471 |

| 25% | NaN | NaN | 39.225000 | 15.600000 | 190.000000 | 3550.000000 | NaN | 2007.000000 | 8433.676950 |

| 50% | NaN | NaN | 44.450000 | 17.300000 | 197.000000 | 4050.000000 | NaN | 2008.000000 | 9954.426135 |

| 75% | NaN | NaN | 48.500000 | 18.700000 | 213.000000 | 4750.000000 | NaN | 2009.000000 | 11537.641963 |

| max | NaN | NaN | 59.600000 | 21.500000 | 231.000000 | 6300.000000 | NaN | 2009.000000 | 18416.870649 |

| species | island | sex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| count | 344 | 344 | 333 |

| unique | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| top | Adelie | Biscoe | male |

| freq | 152 | 168 | 168 |

Grouping and transforming your data

What if we want to use one of the categorical variables in our data as a factor level to calculate our summaries? For example, we may want to separately get the mean flipper length of each species of penguin. In order to do this, we need to do the following things:

- Split our data into different groups (e.g. based the values in the

speciescolumn) - Apply some function (aggregation or transformation)to each group in our data (e.g. calculates the mean)

- Combine each group back together into an output object

We input the column we want to group by into the .groupby() method. This creates a grouped dataframe object that acts like the regular dataframe, but is split into groups based on the column we specified.

<pandas.core.groupby.generic.DataFrameGroupBy object at 0x1907d8590>

We can see that on its own this is not especially useful, as grouping the DataFrame does not produce a new DataFrame (just this weird output message telling us that this is a DataFrameGroupBy object). In order to output a DataFrame, we need to pass the grouped DataFrame to some function that aggregates or transforms the data in each group.

We group our data, select the column we want to aggregate (in this case, flipper_length_mm) and apply the .mean() function to it:

#Note the square brackets around the column name

penguins.groupby('species')['flipper_length_mm'].mean()

species Adelie 189.953642 Chinstrap 195.823529 Gentoo 217.186992 Name: flipper_length_mm, dtype: float64

When we apply the .mean() method to the grouped dataframe, it returns a Series object with the mean flipper length of each species. The exact details of whether pandas returns a groupby object as a Series or a DataFrame gets a little technical; for our purposes, just know that you can make sure the returned object is converted to a DataFrame (which is usually most convenient) by using the .reset_index function:

| species | flipper_length_mm | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | 189.953642 |

| 1 | Chinstrap | 195.823529 |

| 2 | Gentoo | 217.186992 |

We can group by multiple columns by passing a list of column names to the .groupby() method (and using reset_index() as before to have it output as a DataFrame):

| species | sex | flipper_length_mm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | female | 187.794521 |

| 1 | Adelie | male | 192.410959 |

| 2 | Chinstrap | female | 191.735294 |

| 3 | Chinstrap | male | 199.911765 |

| 4 | Gentoo | female | 212.706897 |

| 5 | Gentoo | male | 221.540984 |

So far we have just been applying the .mean function to our groups, but we can use other functions as well! One very useful function to know when grouping is .size(), which will return the number of rows in each group.

species sex

Adelie female 73

male 73

Chinstrap female 34

male 34

Gentoo female 58

male 61

dtype: int64

Exercise: Use grouping to answer the following question about the penguins dataset: Which island has the most Adelie penguins?

Hint: Think about which order you should group by for the most readable output

species island

Adelie Biscoe 44

Dream 56

Torgersen 52

Chinstrap Dream 68

Gentoo Biscoe 124

dtype: int64

Now try your previous code with the order of the columns to group by switched. What changes?

island species

Biscoe Adelie 44

Gentoo 124

Dream Adelie 56

Chinstrap 68

Torgersen Adelie 52

dtype: int64

This shows us that grouping occurs hierarchically, meaning pandas groups data in the order that you specify in! In our case the result is the same (i.e. the counts are equal no matter which column you group on first), but one way is more readily readable for our question than the other.

There are niche situations where it might matter, e.g. your aggregation function depends on the order of values (e.g. if you are sorting your grouped data), or you are doing some non-commutative operation, but generally speaking the results will be the same.

Exercise: now that we have an understanding of pandas, let's go back to our initial example! Calculating the average body mass (in kg) of each penguin species, by sex. We are aiming to reproduce the table below:

Make sure you end up with a DataFrame and not a Series.

| species | sex | body_mass_kg |

|---|---|---|

| Adelie | female | 3.368836 |

| Adelie | male | 4.043493 |

| Chinstrap | female | 3.527206 |

| Chinstrap | male | 3.938971 |

| Gentoo | female | 4.679741 |

| Gentoo | male | 5.484836 |

penguins["body_mass_kg"] = penguins["body_mass_g"] / 1000

penguins.groupby(['species', 'sex'])["body_mass_kg"].mean().reset_index()

| species | sex | body_mass_kg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | female | 3.368836 |

| 1 | Adelie | male | 4.043493 |

| 2 | Chinstrap | female | 3.527206 |

| 3 | Chinstrap | male | 3.938971 |

| 4 | Gentoo | female | 4.679741 |

| 5 | Gentoo | male | 5.484836 |

Exercise: using the

.max()function, find the largest bird on each island.

island Biscoe 6300.0 Dream 4800.0 Torgersen 4700.0 Name: body_mass_g, dtype: float64

Seaborn

Plotting with Seaborn

In addition to knowing how to import and manipulate data, we often want to also visualize our data. There are many tools available that are specialized in plotting data, such a R and ggplot, Excel, etc., but often it can be helpful to do some quick visualization in python as part of a pipeline. The "classic" way to do this is using the matplotlib library, but for this workshop we are instead going to use seaborn, which is based on matplotlib but has (in our opinion) better syntax (being somewhat reminiscent of ggplot, a commonly-used R library), and is specially designed to integrate with pandas.

Plotting can get quite complicated, so we are going to stick to some more "cookie-cutter" implementation that is geared more towards exploratory analysis, rather than making publication-quality figures.

Just as before, it can be helpful to think about what your end goal looks like. Let's say I want to end up with a scatterplot that shows bird bill length relative to body weight, with the color of each point corresponding to bird species, and the shape of the point corresponding to bird sex. With that goal in mind, let's look at syntax.

Defining the Data

We are going to continue using our penguins data set. seaborn has numerous functions for drawing different plots, summarized in the figure below. There are three different broad "families" of seaborn plots, which are shown in the figure below:

relplotplots show relationships between variablesdisplotshow distibutionscatplotplot categorical data

Each plot function within a family usually has similar syntax, as they represent data in similar ways. To create a plot, we call one of these functions and specify our (pandas) dataframe and which columns to encode in which axis. For example, if we wanted a histogram:

penguins = pd.read_csv('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/rfordatascience/tidytuesday/main/data/2020/2020-07-28/penguins.csv')

penguins.head()

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.1 | 18.7 | 181.0 | 3750.0 | male | 2007 |

| 1 | Adelie | Torgersen | 39.5 | 17.4 | 186.0 | 3800.0 | female | 2007 |

| 2 | Adelie | Torgersen | 40.3 | 18.0 | 195.0 | 3250.0 | female | 2007 |

| 3 | Adelie | Torgersen | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2007 |

| 4 | Adelie | Torgersen | 36.7 | 19.3 | 193.0 | 3450.0 | female | 2007 |

<Axes: xlabel='flipper_length_mm', ylabel='Count'>

We can see that for this type of plot, we only need to encode a single column (for the x-axis), but other types of plots might require additional axes. For example, a boxplot needs both an x and y axis defined:

<Axes: xlabel='species', ylabel='bill_length_mm'>

Documentation for each plot type is on seaborn's website, and it lists all required and optional arguments for each plot function: seaborn

Changing plot aesthetics

We can do much more useful things than just setting the x and y axis, however! We will frequently want to group our data, e.g. by species, by sex, etc., and change the plot aesthtics to reflect these groups. To do this, we add an additional argument that specifies which column in our data frame that we want to group on. For example, to color the bars on our histogram based on species, we would use the hue argument:

<Axes: xlabel='flipper_length_mm', ylabel='Count'>

We can see we have changed the colors of the bars, but as they are overlapping it is difficult to read. If we dig into the documentation of the histplot function, we can find that there is also the multiple argument, which changes how overlapping bars behave...let's make them stack instead of overlap:

<Axes: xlabel='flipper_length_mm', ylabel='Count'>

Exercise: check the documentation page for the

scatterplotfunction, and see if you can figure out how to make a scatter plot that shows bird bill length relative to body weight, with the color of each point corresponding to bird species, and the shape of the point corresponding to bird sex.

<Axes: xlabel='bill_length_mm', ylabel='body_mass_g'>